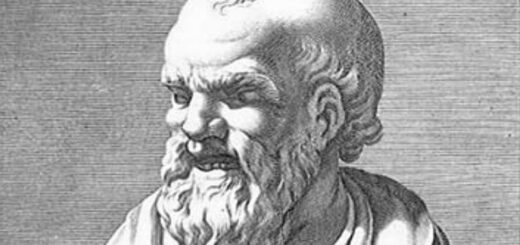

The Philosopher God – XENOPHANES

Gods resemble the humans who created them; mythology is a product of human imagination. This thought belongs to Xenophanes (570–475 BCE), a philosopher who opposed polytheism. If gods resemble humans, meaning they are anthropomorphic, then they are not morally superior to humans. In that case, should they be worshipped? Xenophanes answers this question himself with a firm “no”.

“Mortals believe that the gods are born like themselves, wear similar clothes, have voices, and bodies. Ethiopians say their gods are snub-nosed and black-skinned, while Thracians believe their gods have gray eyes and red hair,” Xenophanes emphasizes. If oxen, horses, and lions had the skill to paint and create art, horses would depict their gods as horses, and oxen as oxen.

Xenophanes also criticized the immoral stories told about gods, especially in the works of Homer and Hesiod. These poets assigned negative traits such as theft, deceit, and adultery to the gods—attributes that are distinctly human.

To the question, Why do humans create gods? Xenophanes gives a simple and rational answer: natural forces. These forces, incomprehensible to humans, evoke fear. Without understanding the language of nature, humanity seeks refuge in the supernatural, leading to the creation of gods. Another reason, he notes, is the fear of death. Unable to reconcile with mortality, humans fall under the influence of religions that promise life after death.

Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis, agrees with Xenophanes in this regard. Freud argued that religion feeds on humanity’s helplessness against the forces of nature and inner instincts. Religion, he believed, emerged in the early stages of human development when reason had not yet taken hold. As a result, humans sought solace in religion to confront these internal and external forces.

Anthropomorphism is the attribution of human form, emotions, and other human characteristics to non-human, supernatural entities. It is a common feature in religion, as almost every known deity possesses some degree of human-like traits.

In Xenophanes’ era, characterized by polytheism, this tendency was especially pronounced. For example, ancient Greek gods loved, married, experienced jealousy and gossip, had children, and rode into battles, distinguishing themselves through their “heroic” exploits.

Two gods who played similar roles in their respective civilizations were Zeus, the chief deity of the Greeks, and Brahma, the central god of Hinduism. Both exhibit numerous human attributes and carry out comparable functions despite existing in vastly different and, likely, unaware civilizations.

Naturally, a logical question arises here: who created whom? Did the gods create humans, or did humans create the gods? This very question was posed by Xenophanes thousands of years ago. He sought its answer and found it.

Human psychology is inherently inclined toward anthropomorphism. Even in modern times, individuals who may not even pronounce the word “anthropomorphism” correctly still attribute human traits to deities. Ideas such as a patient god, an all-seeing god, or a vengeful god are examples of this tendency.

Let us return to Xenophanes.

At a young age, the philosopher left his hometown of Colophon, located in Asia Minor, and spent 67 years traveling through Ancient Greece. During his journeys, he encountered numerous religions and their deities. Xenophanes critically analyzed each one. The experiences and knowledge he amassed during his travels played a leading role in his critique of religion and society.

Let us imagine there are many gods. In that case, they would have to surpass one another in certain aspects while being inferior in others. This would strip them of divinity, as a god by nature cannot tolerate being subject to others. On the other hand, if they were equally powerful, they would not be gods either, for a god must surpass everyone. Equality implies neither superiority nor inferiority. If gods existed in plurality, they could not possess the ability to do everything. Thus, if a god exists, it must be singular, Xenophanes reasoned, constructing a logical chain that led him to conclude that there must be only one god.

This singular god, according to Xenophanes, neither resembles humans in appearance nor intellect. Instead, it is intelligence, reason, and eternity. This god is eternal and unchanging. Like the universe, it has neither come into being nor will it perish. It is infinite.

If the universe and god were created, there would have had to be a time before their creation, but this is impossible. Something cannot come into existence from nothing. Xenophanes’ theology closely resembles pantheism, which regards nature and the universe as divine. This perspective rejects the notion of an anthropomorphic or supernatural deity.

Pantheism was later revived in the Middle Ages by the Dutch philosopher Baruch Spinoza, who developed it into a liberating philosophy. Spinoza proclaimed, “When you harm nature, you harm God; when you harm another person, you harm yourself. The human body is a part of God’s body, and when we harm others, we harm ourselves. Our individual happiness depends on the happiness of all.” This is how Spinoza promoted pantheism as a unified and harmonious worldview.

Xenophanes introduced the concept of the “philosopher god,” a deity omnipresent and governing the universe through its intellect. He described it as follows – The one god, greatest among gods and men, neither resembles mortals in form nor thought. Always remaining in the same place, it moves not at all, nor does it wander to different locations. With the power of its mind alone, it effortlessly causes all things to tremble. Through its entire being, it sees, thinks, and hears everything.

Xenophanes demanded that his ideas be regarded solely as approximations to truth, stating, “Even my words, consider them only as being in alignment with truth, not absolute truth itself.“ This humble acknowledgment of human limitation positions Xenophanes as a forerunner of epistemology.

Epistemology is the branch of philosophy that investigates the nature, origin, and limits of knowledge. Xenophanes’ views suggest that even if someone discovered ultimate truth, they might be unable to recognize it. Similarly, those who think they possess perfect knowledge might be unaware of its full implications.

For Xenophanes, humanity’s role is merely to speculate and interpret. He argued that truth lacks definitive criteria, emphasizing the distinction between belief and knowledge. Belief is subjective and uncertain, while knowledge strives for objective certainty but may always fall short.

This perspective laid the groundwork for philosophical skepticism, a school of thought that questions the possibility of absolute knowledge. Xenophanes’ insights highlight the limitations of human understanding, urging humility in our claims about reality and a continuous pursuit of deeper inquiry.

Skepticism questions the possibility of knowledge and places doubt at the core of its principles. It has evolved from ancient times to the present and continues to be a focal point of philosophical discourse.

Imagine a biologist removing a human brain, placing it in a solution-filled flask, and connecting its neurons to a computer. The computer generates impulses identical to those the body would transmit to the brain, simulating reality. The brain, unaware of the absence of its body, perceives this virtual world as real. This scenario illustrates a central claim of skeptics: humans cannot be certain that the information they receive about their surroundings is objective or authentic.

Xenophanes was the first to distinguish between thought and knowledge. While this distinction seems obvious, many people, even today, confuse their opinions with knowledge. Opinions should be rooted in pre-existing, analyzed data; otherwise, they are hollow, less useful than a vacuum.

Xenophanes’ philosophical ideas shaped several enduring epistemological questions, such as the permanence of matter versus its changing manifestations, the primordial substance underlying the universe, and the diversity of physical forms.

Xenophanes viewed understanding the divine as beyond human capacity, leading him to divide philosophy into two parts: natural philosophy (focused on physical phenomena) and non-material philosophy (exploring abstract concepts).

While acknowledging the importance of water and the sea, Xenophanes disagreed with Thales’ assertion that water is the fundamental principle of all things. He argued for the primacy of earth, noting evidence such as seashells and fish imprints found in rocks, which suggested periodic submersion of land under water.

Xenophanes proposed that all living beings, including humans, originate from a combination of earth and water. He concluded that all creatures return to the earth and that the earth itself emerged from water.

Xenophanes believed the cosmos to be infinite, with celestial bodies like the Sun and stars being purely physical objects rather than divine entities. He also explained clouds as vaporized water, with rain resulting from its condensation—eliminating the need for supernatural explanations.

This view challenges the practice, still observed in some cultures, of invoking divine intervention for rain. As one great thinker remarked: “A person who wastes even an hour of their time has yet to understand the true meaning of life.”

Xenophanes’ rational approach underscores the necessity of applying reason and observation to comprehend the world, laying a foundation for scientific inquiry and modern skepticism.