Anaximander and Anaximenes

Written Greek philosophy begins with Anaximander (610–546 BCE), who was the first philosopher to document his thoughts in writing. The Milesian sage’s book On Nature is considered the first scientific work of ancient Greece. However, only a fragment of it has survived to our time.

Anaximander was a student of Thales and another prominent representative of the philosophical school of Miletus, founded by his teacher. Like Thales, Anaximander was a proponent of science and deeply committed to understanding the cosmos through observation and rational analysis.

The Earth is the center of the universe, believes Anaximander, much like Thales. However, while Thales posited that our planet rests on water, Anaximander reached a different conclusion. He asserted that the Earth is not supported by any pillars. This idea represents one of the greatest cosmological concepts of its time.

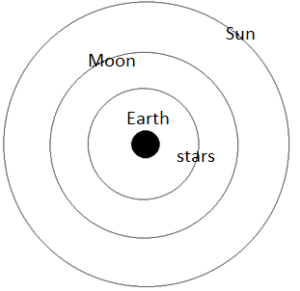

Anaximander was the first philosopher to conceive a mechanical model of the world. According to this model, celestial bodies—including planets, their moons, and stars—move along circular trajectories. They are arranged in layers, one behind the other. The Earth, positioned at the center of the universe, has a cylindrical shape and remains in free motion. As we see, the Greek sage laid the foundation for the first geocentric model in the history of astronomy.

Anaximander’s Universe

Certainly, to a modern intellectual, this theory might seem unprofessional, but 2,500 years ago, it was a groundbreaking idea. Even Aristotle viewed it as such. Though not entirely accurate, this theory sparked the first revolution in cosmology.

After all, the Earth truly does not rest on any pillars and moves freely. This marked the initial steps of applying scientific reasoning to study the universe. It is precisely this concept that grants Anaximander the title of “Father of Cosmology.” Considering contemporary flat-earthers, we can only admire and applaud the ancient sage who reached such a conclusion solely through the power of his intellect 25 centuries ago.

Anaximander, continuing the natural philosophy of the Milesian school, believed that the universe evolves freely, without divine intervention.

The philosopher sought not only to understand the structure of the cosmos but also its origins. He concluded that existence arises from an infinite, eternally moving substance known as the apeiron. This was Anaximander’s answer to philosophy’s first and fundamental question.

Objects, according to him, originate from this substance and eventually disintegrate back into it. While Thales identified a primordial substance (water) that transforms into other forms of matter and perishes, the apeiron, in contrast, is eternal, merely taking on various forms.

Anaximander’s theory would later play a central role in the development of the concept of matter.

As we see, the apeiron is not one of the existing forms of matter around us, nor is it similar to anything we know. Anaximander arrived at this conclusion through simple deduction, as the apeiron lies beyond direct observation.

Logic demands that the apeiron be infinite, as nature’s evolution and the universe itself are infinite. Consequently, the primordial substance must also be infinite; otherwise, it would be depleted. According to the philosopher, the transformation of the apeiron into matter occurs as a result of eternal motion.

In the future, we will encounter this theory again.

Anaximander speculated about the origins of life, suggesting that living organisms emerged from sediment on the dried seabed and later moved onto land. He claimed that the first living creatures resembled fish with spiny skin. This implies that life itself originated without any supernatural intervention.

If the reader perceives the early breath of evolutionary theory in this, they are not mistaken—and may even take pride in their intellect. But not excessively; avoid harmful euphoria. After all, a truly intelligent person is aware of their intellectual boundaries. Euphoria might blur these boundaries, and believing the mind to be limitless is the first symptom of foolishness.

Time, Anaximander argued, is eternal and ageless. The universe, on the other hand, is like a living organism—it is born, grows, ages, and dies, only for the cycle to repeat.

Anaximander’s thoughts about the universe show certain alignments with modern science. The contemporary Big Bang model, which provides the most comprehensive explanation of the universe, suggests he was not entirely mistaken. According to this model, the observable universe originated 13.8 billion years ago and has been expanding ever since[1]. The theory also proposes possible scenarios for the eventual fate of the universe.

Let’s return to the beginning.

Anaximander did not merely study time—he managed to harness it. According to some sources, he invented the first sundial, the gnomon. Other accounts suggest he introduced this device from ancient Babylon to Greece.

The gnomon is the oldest astronomical instrument, used to measure the Sun’s altitude and determine time.

The Greek philosopher proposed the hypothesis that there are numerous worlds beyond Earth, some of which may also harbor life. He asserted that these worlds emerge and perish, making him the founder of cosmic pluralism. Cosmic pluralism is the theory suggesting the existence of countless other planets, possibly hosting life. A simple calculation supports this idea. Our galaxy contains over 100 billion stars, some of which are similar to the Sun in type[2]. This similarity implies that if a habitable planet can form around a star like our Sun, the same process could occur around other stars. This hypothesis is far from illogical. And this is just within our galaxy.

In the observable universe, or metagalaxy, there are up to two trillion galaxies[3].

For anyone familiar with these numbers—like us—it is not difficult to conceive the idea of multiple worlds. However, 25 centuries ago, Anaximander was unaware of these figures.

The core of Anaximander’s hypothesis of multiple worlds lies in the blow it delivers to human ego: Earth, life, and ultimately humanity are not unique. And as everyone should understand, what is not unique cannot be ideal or perfect.

To achieve perfection, one must continuously evolve and strive for greater heights. Only then can we become beings worthy of the grandeur of the cosmos. Only then can we become true philosophers! Perhaps even the Übermensch may emerge. Humanity must transcend itself, climbing not backward but toward the Übermensch. Such is the primary message of philosophy.

Even the ape grew weary of itself and climbed toward humanity. Climbing forward, not back, is imperative—to the stars and beyond. Earth should be a springboard, not a dwelling. Otherwise, it will become a pit, a dark abyss lost in time.

Humankind, failing to understand this, will inevitably be lost in that darkness.

Another member of the Milesian school of philosophy is Anaximenes (ca. 585–525 BCE). Following the same trajectory, he develops his cosmological model. The central idea of his model is that existence originates from air because air is infinite and divine. According to the philosopher, every being is a different form of air. What Thales saw in water, Anaximenes saw in air.

Anaximenes not only identifies air as the primal substance but also proposes a mechanism for the formation of surrounding objects. Air, in perpetual motion, must either condense or rarefy. Rarefaction produces fire, while condensation results in solid substances like stone, earth, and water. Anaximenes thus perceives a relationship between heat and the density of matter. As evidence, he suggests that warm wood is less dense, while cold stone is denser.

Thus, Anaximenes introduces the theories of condensation and rarefaction. These opposing processes form the basis for the various states of matter. His greatness lies not merely in the ideas he proposes but in the logical reasoning he employs to support them.

Thales, Anaximander, and Anaximenes define philosophy’s first problems—what is the primal substance, and how does it transform into matter? Each offers their own answer. This marks the birth of Greek philosophy. The next generation of philosophers will begin their work by seeking answers to these same questions. Over centuries of evolving discourse, philosophy, science, and humanity will emerge as the ultimate victors.

[1] https://www.mpg.de/7044245/Planck_cmb_universe

[2] https://www.space.com/25959-how-many-stars-are-in-the-milky-way.html

[3] Fountain, Henry. “Two Trillion Galaxies, at the Very Least”. New York Times, 2016